Last updated on 2025-12-02 at 18:00 EST (UTC-05:00)

Safety Fundamentals for the New Amateur Radio Operator: A Machinery-Safety Engineer’s View

As I continue my journey into amateur radio, one thing has struck me more than anything else: how familiar so much of this territory feels from decades spent working in machinery safety, electrical safety, bonding, and earthing. Whether I’m assessing a press line in a factory or installing a transceiver in my shack, the underlying principles are essentially the same. You’re still dealing with fault currents, leakage paths, thermal hazards, shock exposure, RF exposure, lightning strikes and the absolute necessity of a well-designed grounding and bonding system for both safety and performance.

image: NOAA

Al Penney’s excellent chapter on safety in the RAC Basic course distills many of these fundamentals for the new amateur operator. What follows is my own take—grounded (pun fully intended) in both the course material and my day-to-day practice in machinery safety.

Why Safety Matters in Amateur Radio

Amateur radio looks deceptively benign from the outside—just a few radios, some feed lines, maybe a tower if you’re lucky. But the risks are very real:

- Mains voltage and high-current DC systems

- Radio frequency (RF) energy exposure

- Lightning surges and induced currents

- Grounding and bonding failures

- Mechanical hazards from towers and masts

- Fire risks from poor wiring or aging equipment

If you’ve spent a career keeping machinery operators out of harm’s way, you quickly recognize that amateur operators can face the same categories of hazards—just scaled differently.

1. Understanding Household and Station Power

Canadian residential electrical systems are built around a 240/120-volt, single-phase, three-wire supply. Two “hot” legs (typically red and black) provide 240 volts between them, and each offers 120 volts relative to the neutral conductor (white). Only the hot conductors are fused or switched—never the neutral.

Older homes can pose surprises: two-prong outlets, ungrounded circuits, knob-and-tube or aluminum wiring, or branch circuits overloaded by modern electronics. All of those bring risks that may only show up under RF load or when connecting a modern transceiver or linear amplifier.

The symptoms of overload are textbook:

- Flickering or dimming lights

- Warm or discoloured receptacle plates

- Frequent breaker trips

- Buzzing or crackling outlets

- A faint burning odour

Each of these is a warning sign that the branch circuit is under stress. In machinery safety, we teach operators to treat “abnormal” as “unsafe.” The same applies here.

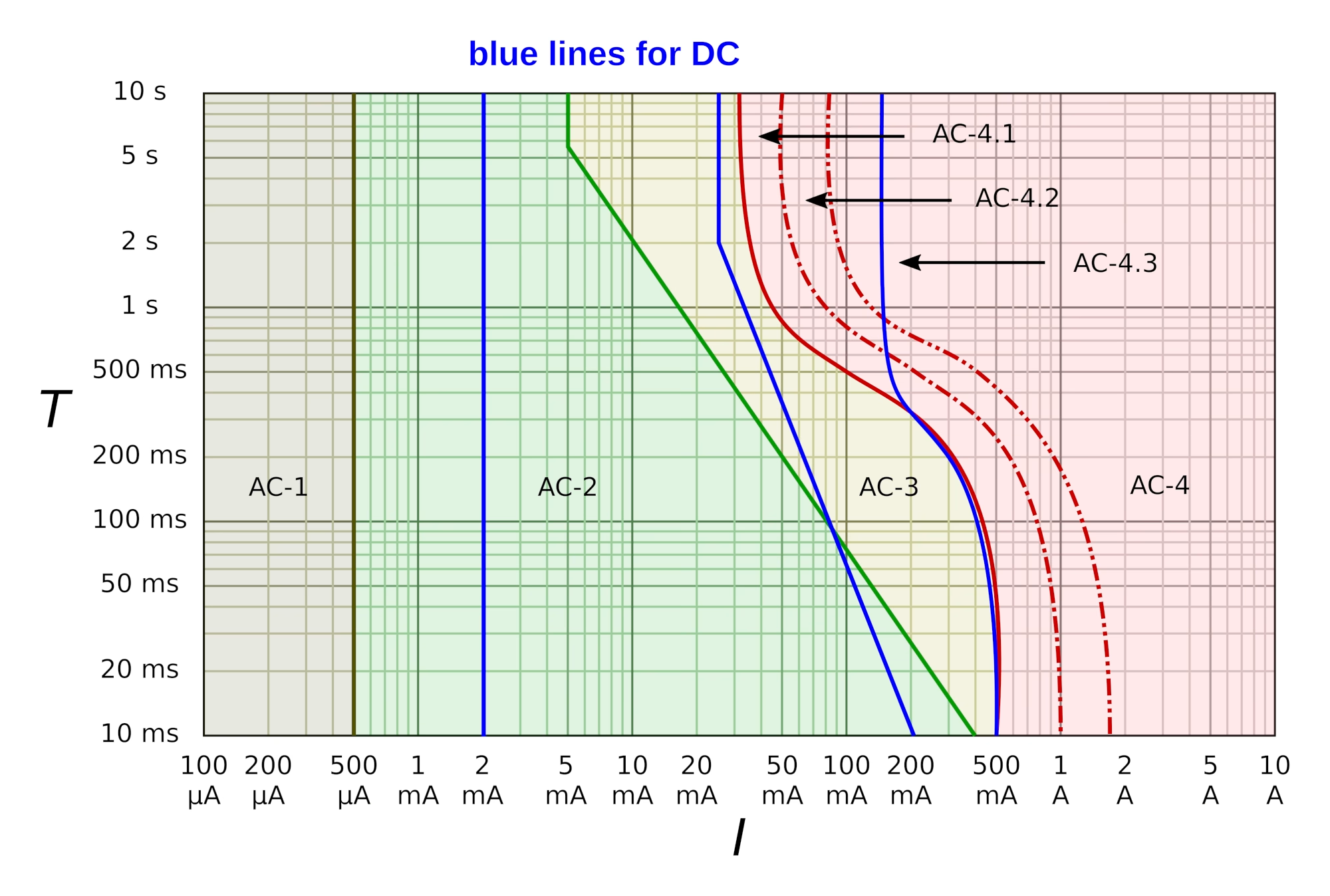

2. Shock Hazards: Understanding the Enemy

We’re conditioned to think of electricity in terms of voltage, but in reality, it’s current that injures or kills. Women and men typically have different thresholds for sensing electrical currents. Women generally have a lower threshold of sensation for electrical currents compared to men, often around 40-43% lower for sensory perception in studies using transcutaneous or surface electrical stimulation[16], [17]. For 60 Hz AC currents through hand contacts, perception thresholds are typically below 1 mA for both genders, with grip contacts as low as 0.4-0.5 mA in adult males and similarly low but slightly reduced in females.[18][19]

Standard electrical safety references indicate:

- Perception/sensation: 0.5-1 mA (tingling sensation possible for up to 10 seconds), with women often perceiving at lower levels due to higher sensory excitability [16], [20]

- Women show consistently lower sensory thresholds across multiple studies, attributed to neurophysiological differences rather than just skin or adipose tissue [17], [21].

Gender Differences

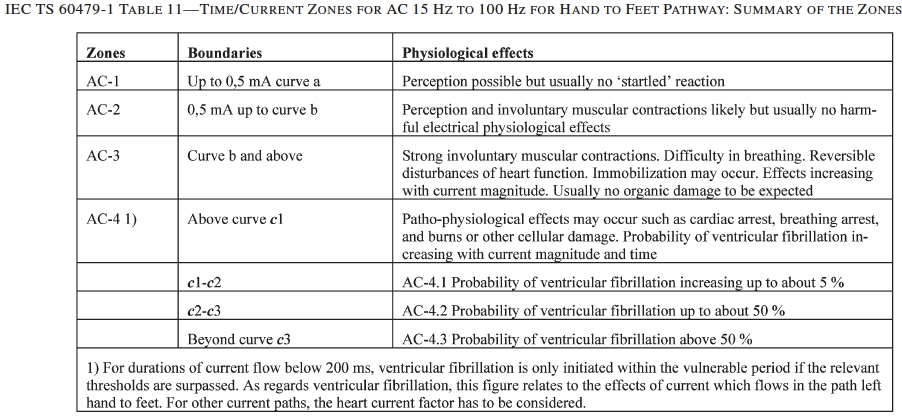

Studies confirm women require less current for initial sensation (e.g., -43% vs. men) and motor responses, though pain perception at higher levels can be more pronounced in women [16], [22]. These thresholds vary by factors such as frequency (AC 50-60 Hz is more perceptible than DC), contact type (grip vs. tap), skin condition, and the current path through the body, but gender disparity persists [18], [23].

Even small currents can be dangerous:

- 0.25 mA creates perceptible tingling

- 10 mA can lock your grip due to muscle tetany

- 20–50 mA across the heart can cause ventricular fibrillation

- >100 mA can cause severe burns and internal injury

At 60 Hz—the frequency of the North American power grid—the human heart is particularly vulnerable because its natural pacing interval is in the same range.

[14, Fig. 4] College Sidekick

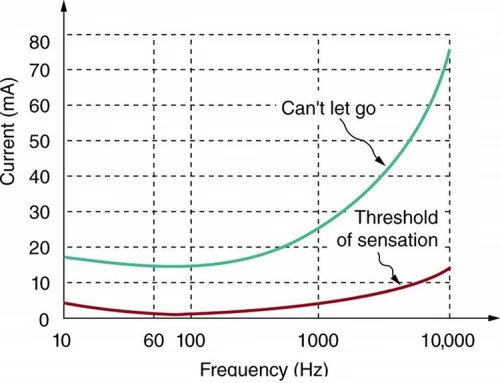

The path through the body is also important—this is where the “one hand rule” when working with high voltages comes from.

By keeping your left hand in your back pocket while working on energized or potentially energized equipment, you eliminate the possibility of introducing current through your left arm which can then travel through your heart to an exit point. Additionally, using an insulating mat rated for the highest voltage you are likely to encounter can help protect against electric shock hazards.

IEC 61140:2016, Protection against electric shock — Common aspects for installation and equipment [15], provides guidance on measures that can be used to reduce the risk of shock.

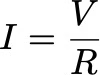

The table below shows the defined limits for some of the voltage bands covered in IEC standards. Except for RF voltages appearing on transmission lines and antennas in operation, everything in the radio shack operates at Low Voltage (LV), below 1000 Vac or 1500 Vdc. The CEC in Canada and the NEC in the USA extend down to 0 Vac or dc, while in the EU, the Low Voltage Directive uses 50 Vac or 75 Vdc as the lower limit.

Damp or wet conditions can reduce the voltage where a shock hazard exists to as little as 6 V.

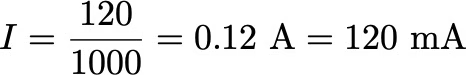

A helpful formula for estimating shock current is Ohm’s Law:

Where:

I = current through the body

V = applied voltage

R = resistance of the body (which can drop below 1000 Ω when the skin is wet)

Thus, a wet human body touching 120 V can experience:

Far into the range of fatal fibrillation.

The impedance of the body is made up of two components:

- Skin resistance

- Internal resistance

Both components can include a capacitive element, which becomes more important as the frequency of the electrical source increases.

| Current path | Dry skin | Wet skin |

|---|---|---|

| ear-to-ear (internal) | 100 Ω | |

| left hand to left foot (internal) | 500 Ω | |

| left hand to left foot | 100 kΩ – 600 kΩ | 1 000 Ω |

At 500 V or more, high resistance in the outer layer of the skin breaks down.

Ways protective skin resistance can be significantly reduced

• Significant physical skin damage: cuts, abrasions, burns

• Breakdown of skin at 500 V or more

• Rapid application of voltage to an area of the skin

• Immersion in water

Al’s advice mirrors good industrial practice: do not approach a shock victim until the circuit is de-energized. Otherwise, you risk becoming the second casualty.

3. Protective Devices: GFI/GFCI, AFCI, and Isolation Transformers

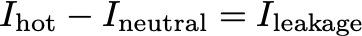

The basic defence against shock hazards in modern wiring is the Ground-Fault Circuit Interrupter (GFCI). A GFCI compares the current in the hot and neutral conductors. If the currents differ by more than about 5 mA, it assumes leakage—possibly through a human body—and disconnects the circuit.

The underlying principle can be expressed as:

Whenever:

—the GFCI trips.

Similarly, the Arc-Fault Circuit Interrupter (AFCI) recognizes series and parallel arcing signatures in conductors—important because many residential fires start with an arc in damaged or aging wiring.

An isolation transformer adds another layer of protection by preventing current from finding a return path through the earth or through a person. In machinery safety, isolation is fundamental for service procedures; the same applies when working on radios.

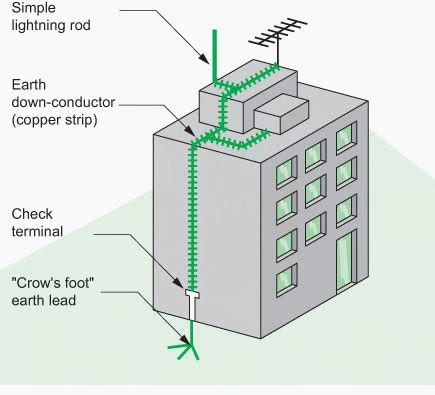

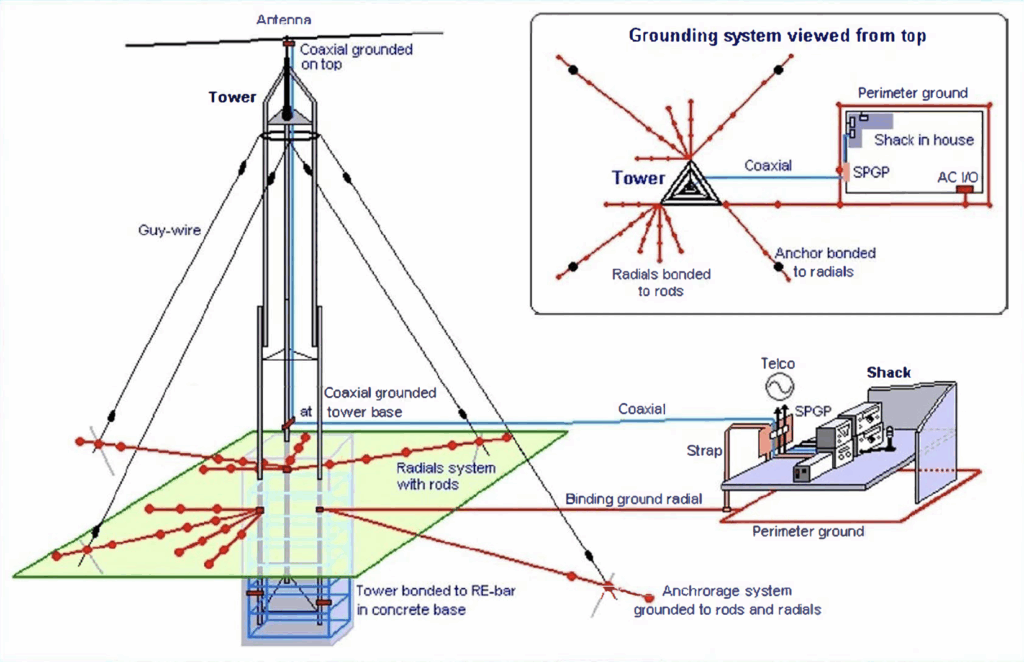

4. The Three Grounds Every Station Needs

Al Penney introduces three distinct ground types for amateur stations:

- AC Safety Ground

The protective earth connection required by electrical codes. This ensures exposed metal stays at earth potential during a fault. - Lightning Ground

Provides a low-impedance path to earth for lightning-induced surges, protecting the structure and equipment. - RF Ground

Provides a low-impedance path at radio frequencies, minimizing RF feedback, interference, and hot spots.

In machinery safety, we typically talk about earthing (fault protection) and bonding (equipotential equalization). Amateur radio requires both, but adds RF behaviour to the equation.

image: Mike Mikelson

Bonding vs. Grounding (Earthing)

- Bonding is the practice of connecting metal components to maintain equipotentiality as much as possible.

- Grounding/Earthing connects the system to the earth reference.

An amateur station must do both; otherwise, circulating currents will cause unpredictable (and occasionally unpleasant) results.

5. RF Grounding: The Hidden Trouble-Maker

Unlike AC grounding systems, RF grounds behave according to wavelength. A conductor approaching ¼ wavelength at the operating frequency becomes a high-impedance point:

Where

λ = wavelength in metres

c = speed of light in a vacuum (300,000,000 m/s)

f = frequency

For example, at 14 MHz (20-metre band):

A quarter-wave is roughly:

A ground strap >5 m long may actually create an RF hotspot rather than eliminate one.

This is why the single-point ground (SPG)—a central bonding bar to which all equipment is connected—is so important. It minimizes circulating currents, reduces RF feedback, and prevents your rig’s microphone or your metal desk from becoming unexpectedly “hot.”

6. Ground Rods and Earth Systems

From a machinery-safety perspective, ground rods in a radio installation behave exactly like the electrodes used in industrial and utility installations. The fundamentals are the same:

- Use copper-clad steel rods

- Length matters (2.4–3.0 m recommended)

- Use UL-listed or CSA-marked clamps

- Use heavy copper conductors (#6 AWG or tinned copper strap)

- Bond cold-water piping only if it is metallic and continuous

But the CEC requires that all grounding electrodes—service ground, lightning protection ground, and any supplemental rods—must be bonded together. Failure to bond grounds is one of the leading causes of destructive surge paths.

7. Lightning Protection: Voltage Equalization is Everything

A lightning strike doesn’t need to hit your tower directly to ruin your equipment. A near strike can induce thousands of volts into cables or wiring. The goal isn’t to “block” lightning—that’s impossible—but to:

- Bring every conductor entering the house to the same potential

- Provide a low-impedance path to earth

- Prevent flashover inside the structure

This is exactly how industrial surge protection works in machinery with long interconnecting cables.

For amateurs, this means:

- Bonding coax shields at the service entry

- Using spark gaps or gas discharge tubes

- Keeping bends in ground conductors smooth and gentle

- Bonding the tower to the station ground system

- Keeping the entry panel (or bulkhead) as close to the station ground as practical

The theme is always the same: equipotential bonding.

8. RF Exposure: What New Operators Need to Know

Radio frequency exposure is regulated because non-ionizing radiation (NIR) can heat tissue, stimulate nerves, and cause cataracts or burns at sufficiently high power densities.

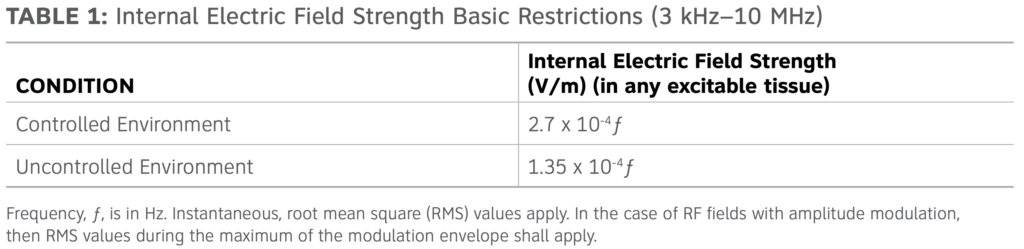

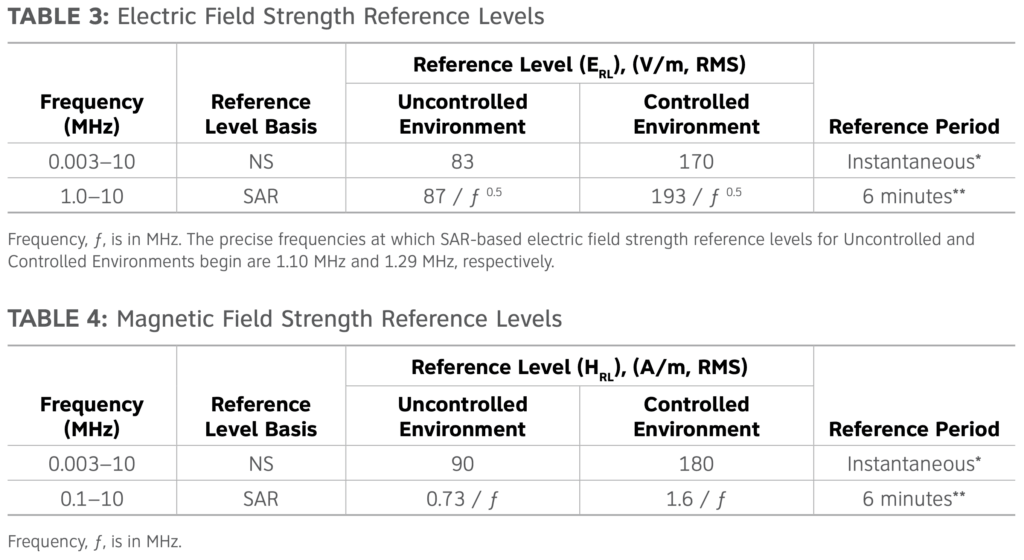

In Canada, we follow Health Canada’s Safety Code 6, Limits of Human Exposure to Radiofrequency Electromagnetic Fields in the Frequency Range from 3 kHz to 300 GHz [33]. This document sets out, in technical terms, the maximum exposure levels that humans can tolerate without causing identifiable harm.

SC6 does not define transmitter power, or effective radiated power (ERP), but rather the intensity of the E- and H-fields. E-fields are measured in volts per metre (V/m) at a specific distance from the source, and H-fields are measured in amperes per metre (A/m). Table 1 from SC6 gives the maximum exposure limits for individuals including occupationally exposed workers and the general public.

Note that the exposure limits in Table 1 are much lower in the Uncontrolled Environment (i.e., the general public) than those in the Controlled Environment (i.e., workers in RF exposed environments).

The basic field-strength relationship is:

Where:

S = power density

PTX = transmitter power

G = antenna gain (linear)

r = distance from antenna

Even a 100-watt HF radio can exceed allowable limits if the antenna is too close or improperly installed.

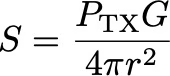

In addition, SC6 includes limits for induced and contact currents as shown in Tables 7 and 8. Induced currents can cause RF shocks and burns.

SC6 has not been updated since 2015, however, the International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection published the Guidelines for Limiting Exposure to Electromagnetic Fields (100 kHz to 300 GHz) [34] in 2020.

The new ISED exposure rules require:

- Station evaluation

- Control of uncontrolled (public) vs controlled (licensee) areas

- Documentation

It’s not onerous—but it needs to be done.

9. Fire Safety, Surge Protection, and Aging Equipment

Surge protectors degrade with every transient. The metal-oxide varistor (MOV) inside slowly changes its characteristics until it fails—sometimes due to overheating. That’s why a surge protector should always have:

- A functioning status indicator

- Internal over-current protection

- Adequate joule rating (≥600 J preferred)

- Proper UL/CSA marking

As Al notes, “daisy chaining” power strips is a known fire hazard. And in a station environment, power strips often operate near their limits due to radios, chargers, tuners, and amplifiers.

If something feels warm under normal load, it’s already trying to tell you something.

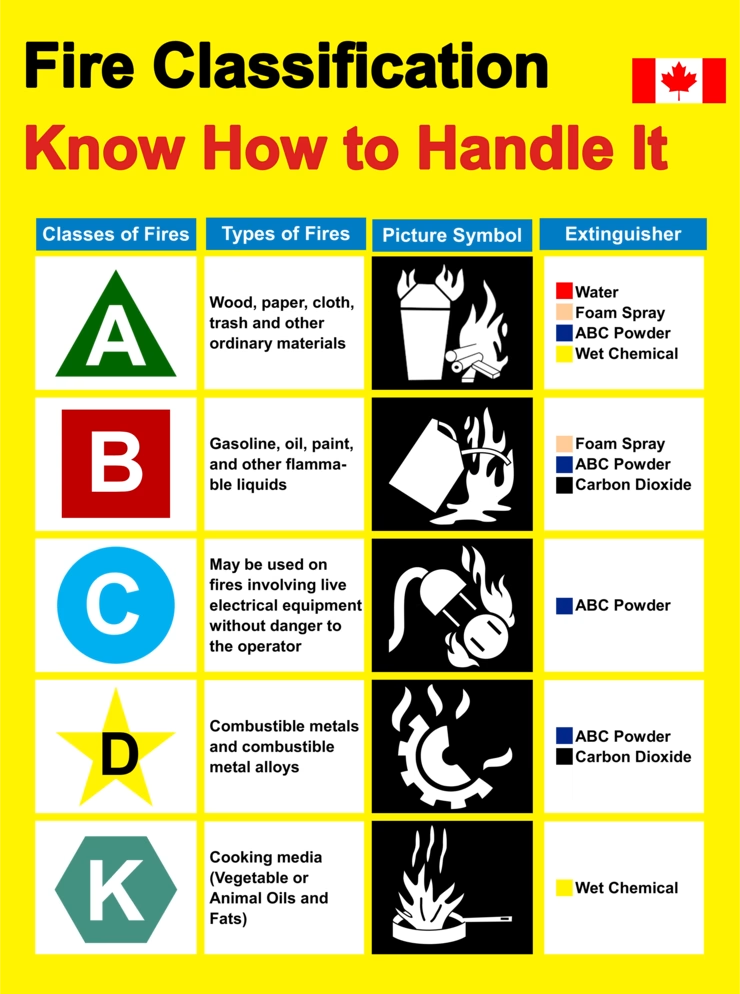

Fire safety

If you are finishing a basement room for use as a radio shack, consider installing a smoke/CO2 detector in the shack, even if there is another one in the basement. This will allow you to close and lock the door when not in use or when kids are around, preventing accidents and unauthorized use of the equipment.

Having a suitable fire extinguisher in the shack is important in case something does catch fire. Either a Type A and Type C extinguisher or a multi-type extinguisher intended for those types of fires should be kept on hand and inspected monthly.

10. First Aid: The Human Side of Electrical Safety

One of the best lines in Al Penney’s chapter is simple:

Do not approach until the power is off.

—Al Penney, VO1NO

Everything after that follows the standard chain of survival used in industrial electrical incidents:

- Ensure the scene is safe

- Disconnect power

- Call 911

- Provide CPR and use an automated external defibrillator (AED) if available

- Treat for shock and burns

It’s worth taking a CPR/AED course—whether for radio, machinery safety, or life in general.

Conclusion: Amateur Radio Safety Is Just Engineering Done Right

One of the reasons I’m enjoying amateur radio so much is that it brings together every part of my engineering background—electrical safety, bonding and grounding, RF, EMC (electromagnetic compatibility), and yes, even some human factors. The same principles that keep machine operators safe apply in the radio shack:

- Keep conductive parts at the same potential

- Control fault paths

- Expect insulation to fail eventually

- Keep conductors short and low-impedance

- Let protective devices do their job

- And above all—respect electricity

Of course, there’s a lot more to say about safety: tower climbing, RF exposure, etc. Safety isn’t a checkbox; it’s a mindset. And as new amateur operators, embracing that mindset early keeps our stations—and ourselves—operating for years to come.

Bibliography

[1] A. Penney, Safety. Royal Amateur Radio Club (RAC) Basic Qualification Course, Chapter 16, VO1NO, n.d. Ch16-Safety

[2] National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), “Home Electrical Fires,” NFPA Reports, 2010.

[3] Electrical Safety Foundation International (ESFI), “Fuse and Breaker Breakdown,” “Switch to Safety,” and “Extension Cords and Power Strip Safety,” ESFI Resources. [Online]. Available: https://www.esfi.org/

[4] Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), “Arc Fault Circuit Interrupters (AFCIs),” CPSC Safety Publications.

[5] Mayo Clinic Staff, “Electrical injuries: First aid,” Mayo Clinic, 2019.

[6] “How to Treat a Victim of Electrical Shock,” WikiHow, 2023.

[7] Hydro-Québec, “What are the effects of electric current on the human body?” Hydro-Québec Safety Resources, 2018.

[8] M. Holt, “Electrical Shock Hazards Explained,” Mike Holt Enterprises, 2002.

[9] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “Worker Deaths by Electrocution,” NIOSH Publication 98-131, 1998.

[10] Reader’s Digest, “CPR 101: These Are the CPR Steps Everyone Should Know,” Reader’s Digest Canada, 2021.

[11] F. Pantridge, “Portable Defibrillation: Early Development and Clinical Use,” Lancet, vol. 286, no. 7424, 1965.

[12] Underwriters Laboratories (UL), UL 1449 – Standard for Surge Protective Devices, 4th ed., UL, 2014.

[13] American Heart Association (AHA), “Hands-Only CPR Guidelines,” AHA CPR & First Aid, 2020.

[14] ‘Electric Hazards and the Human Body’, College Sidekick — Physics. [Online]. Available: https://www.collegesidekick.com/study-guides/physics/20-6-electric-hazards-and-the-human-body

[15] Protection against electric shock — Common aspects for installation and equipment, IEC 61140. Geneva: International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). 2016.

[16] Differences in electrical stimulation thresholds between … https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18300313/

[17] Differences in electrical stimulation thresholds between men and women https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ana.21346

[18] J. C. Keesey, F.S. Letcher. “Human Thresholds of Electric Shock at Power Transmission Frequencies.” Arch. Env. Health. Vol. 21. 1970. Available: https://zoryglaser.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/HUMAN-THRESHOLD-OF-ELECTRIC-SHOCK-AT-POWER-TRANSMISSION-FREQUENCIES.pdf [Accessed 2025-11-30]

[19] Minimum Thresholds for Physiological Responses to Flow of Alternating Electric Current Through the Human Body at Power-Transmission Frequencies, Naval Medical Research Institute. 1969. Available: https://zoryglaser.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/MINIMUM-THRESHOLDS-FOR-PHYSIOLOGICAL-RESPONSES-TO-FLOW-OF-ALTERNATING-ELECTRIC-CURRENT-THROUGH-THE-HUMAN-BODY-AT-POWER-TRANSMISSION-FREQUENCIES-NMRI.pdf [Accessed: 2025-11-30]

[20] Safe Levels of Current in the Human Body Available: https://www.d.umn.edu/~sburns/EE2212/L-Safe-Levels-of-Current-in-the-Human-Body.pdf [Accessed 2025-11-30]

[21] Sex and age differences in sensory threshold for … Available: https://www.scielo.br/j/fm/a/FkPdhzvxmxLcZ7QXjsjCGLz/?format=pdf&lang=en [Accessed 2025-11-30]

[22] Differences in electrical stimulation thresholds between … Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ana.21346 [Accessed 2025-11-30]

[23] Let Go Current | IE Rule – Estimation and Costing Available: https://www.electricalje.com/2024/12/let-go-current-ie-rule-estimation-and.html [Accessed 2025-11-30]

[24] “Gender Differences in Current Received during Transcranial Electrical Stimulation”. Frontiers. Available: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00104/full [Accessed 2025-11-30]

[25] “HUMAN RESPONSES TO ELECTRICITY “. Available: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/19730001338/downloads/19730001338.pdf [Accessed 2025-11-30]

[26] “Factors Affecting and Adjustments for Sex Differences in Current Perception Threshold With Transcutaneous Electrical Stimulation in Healthy Subjects”. Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ner.12889 [Accessed 2025-11-30]

[27] “The effects of high electric current on the human body”. Available: https://betacomearthing.com/resources/the-effects-of-high-electric-current-on-the-human-body/ [Accessed 2025-11-30]

[28] E. Dölker, S. Lau, M. A. Bernhard, J. Haueisen. “Perception thresholds and qualitative perceptions for electrocutaneous stimulation”. Available: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9072403/ [Accessed 2025-11-30]

[29] “AC & DC Electric Shocks – Electrical Energy in the Home”. Available: https://eliotsphysics.weebly.com/ac–dc-electric-shocks.html [Accessed 2025-11-30]

[30] S. Seno, H. Shimazu, E. Kogure, A. Watanabe, H. Kobayashi. “Factors Affecting and Adjustments for Sex Differences in Current Perception Threshold With Transcutaneous Electrical Stimulation in Healthy Subjects”. Available: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6766980/ [Accessed 2025-11-30]

[31] I. Lund, T. Lundeberg, J. Kowalski, L. Svensson. “Gender differences in electrical pain threshold responses to transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS)”. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15670645/ [Accessed 2025-11-30]

[32] “Characteristics of current perception produced by intermediate-frequency contact currents in healthy adults”. Frontiers. Available: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnins.2023.1145505/full [Accessed 2025-11-30]

[33] ‘Limits of Human Exposure to Radiofrequency Electromagnetic Fields in the Frequency Range from 3 kHz to 300 GHz’. Ottawa: Health Canada. 2015. Available: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/migration/hc-sc/ewh-semt/alt_formats/pdf/consult/_2014/safety_code_6-code_securite_6/final-finale-eng.pdf [Accessed: 2025-12-01]

[34] ‘Guidelines for Limiting Exposure to Electromagnetic Fields (100 kHz to 300 GHz)’, Health Physics, vol. 118, no. 5, pp. 483–524, May 2020, doi: 10.1097/HP.0000000000001210. Available: https://www.icnirp.org/cms/upload/publications/ICNIRPrfgdl2020.pdf [Accessed: 2025-12-31]

Leave a Reply