Building the Heart of the Shack

When I was starting out in electronics in the mid-1980s, the idea of having a well-equipped radio shack had a kind of magic to it (it still does!).

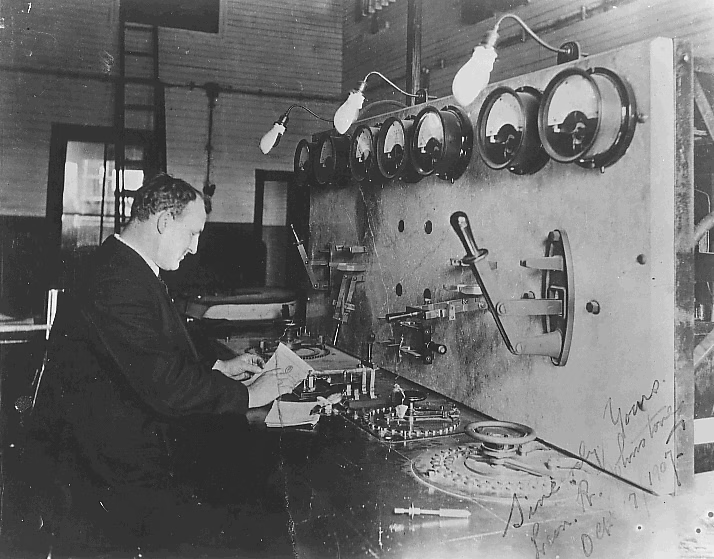

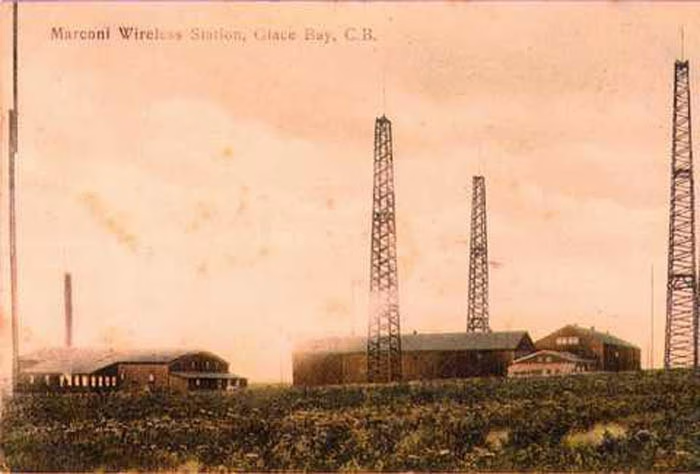

At GFC Hammond in Guelph, where I first worked as a production test technician, I’d wander through the Hammond Museum of Radio on my lunch breaks, looking at the early receivers and transmitters that once connected Canada to the world. Those glass-tubed wonders seemed impossibly far from my world of circuit boards and switching supplies—but they planted the seed.

Now, after years of working with safety systems, standards, and industrial controls, I find the simplicity of amateur radio refreshing. It’s a space where you can still build something tangible—wire, solder, and ingenuity turning into a working station that reaches across continents.

Choosing the Right Space

Al Penny starts Chapter 11 of the RAC course with a point that sounds simple but matters immensely: location is everything. Whether your shack is in the basement, a spare room, or tucked into a corner of your office, comfort, safety, and practicality all count. I’ve seen too many setups crammed into damp basements where corrosion becomes a silent saboteur. On the flip side, attic shacks turn into saunas by July. [1]

The key is access—to power, grounding, and a clean route for feed lines and rotator cables. The rest—furniture, décor, and clever cable management—comes later. What matters most is making a space you actually want to spend time in. After all, this is where you’ll chase DX at 2 a.m., rebuild an antenna tuner that “worked fine yesterday,” and tinker endlessly with wiring diagrams.

The Gear: New, Used, and Everything in Between

Penny gives solid advice on buying equipment: define your needs first, then go shopping. The market today is overflowing with excellent radios, from handhelds that fit in a jacket pocket to sophisticated HF rigs that rival commercial equipment. The temptation to overspend is real.

Buying used gear can be a fantastic way to stretch your budget—but it’s a bit like dating. You need to know what you’re getting into. Check for drift, dirty switches, and tell-tale signs of neglect. A radio that looks like it’s been through a sandstorm probably has. But when you find the right piece—an older Icom or Kenwood that’s been well-loved and well-maintained—it can serve faithfully for years.

Whether you buy new or used, read the reviews, talk to other hams, and don’t underestimate the value of a dealer warranty. Sometimes peace of mind is worth a few extra dollars.

The Joy of Hamfests

There’s no better way to get your hands on gear—and stories—than at a hamfest. From Dayton’s legendary Hamvention to our own HAM-EX and York Region shows here in Ontario, these events are part swap meet, part social gathering, and part carnival. You might arrive looking for a particular SWR meter and leave with a trunk full of mystery boxes and a new circle of friends.

It’s that mix of technical curiosity and community that keeps this hobby alive. Long before online marketplaces and Discord chats, the hamfest was where you learned, traded, and laughed with people who spoke your language—literally and figuratively.

The Supporting Cast

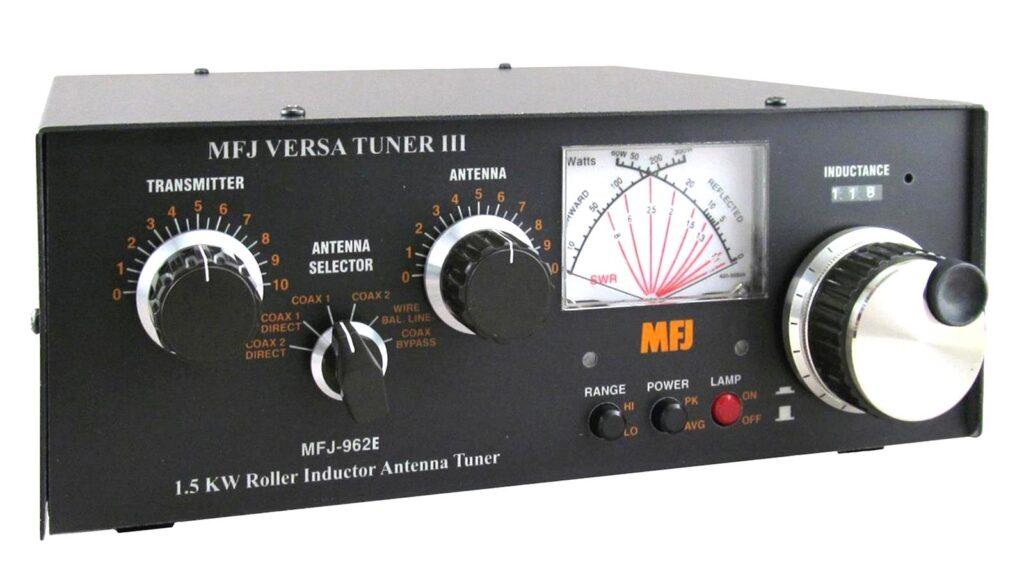

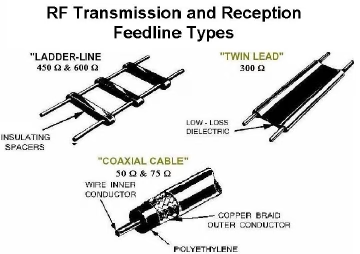

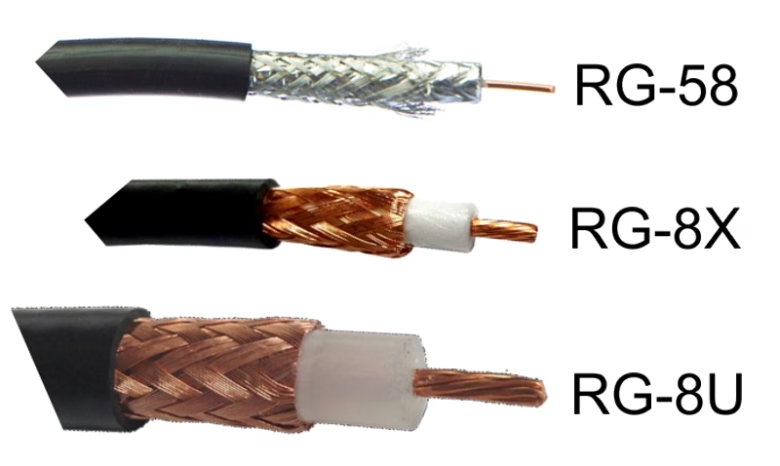

A good station isn’t just a transceiver and a mic. Penny’s chapter reads like a love letter to the small but vital accessories that make a station run smoothly: the SWR meter, the dummy load, the antenna tuner, and those ingenious antenna switches that save you from untangling coax spaghetti. Each one has a role in keeping the station efficient, safe, and operational.

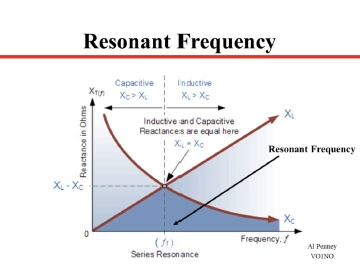

His explanation of the antenna tuner—how it doesn’t “tune the antenna” at all but instead tricks your transmitter into seeing the load it wants—is a reminder of how much practical wisdom hides in this hobby.

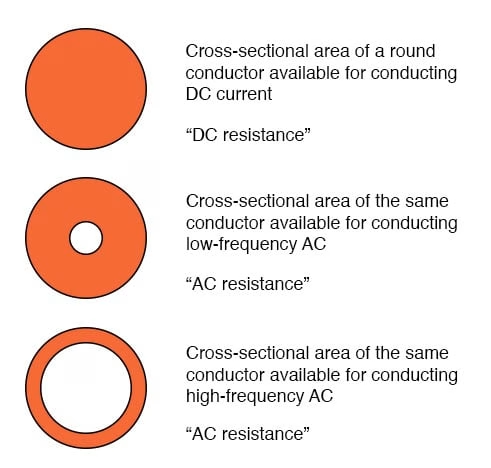

You learn theory, sure, but you also learn the gentle art of “coax diplomacy”: keeping your rig happy, your feedline loss low, and your neighbours blissfully unaware of their TV flickering every time you key up.

A Final Thought

In an age of plug-and-play everything, there’s something grounding—literally and figuratively—about building your own station. Each choice, from desk height to antenna orientation, reflects your habits and curiosity. You can buy the fanciest SDR on the market, but it won’t mean much until you’ve wrestled with grounding straps, tuned an antenna by ear, and smelled a resistor or two giving up the ghost.

For me, that’s the heart of amateur radio: hands-on, imperfect, and wonderfully human. Every station tells a story—not just of frequencies and filters, but of persistence, learning, and connection.

Bibliography

[1] A. Penney, ‘Establishing and Equipping a Station’, presented at the RAC Basic Certificate Course, Radio Amateurs of Canada, Canada, Nov. 02, 2025. Accessed: Nov. 02, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.rac.ca/

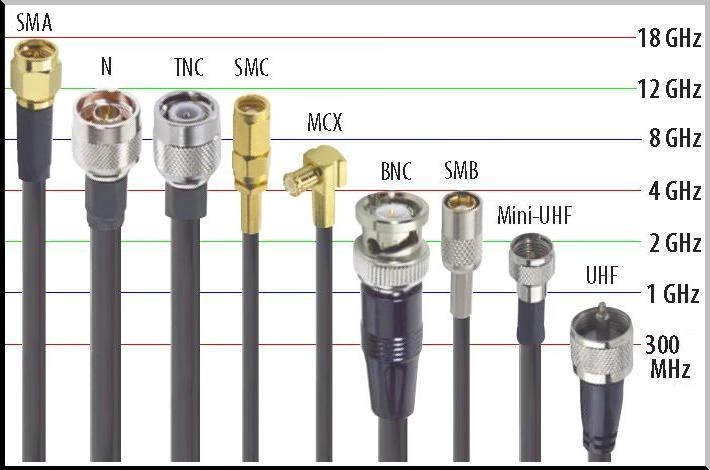

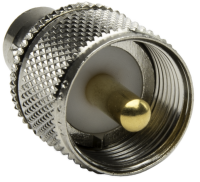

(pin with threads inside)

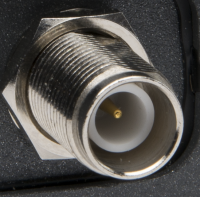

(pin with threads inside) (socket with threads outside)

(socket with threads outside) (pin with threads inside)

(pin with threads inside) (socket with threads outside)

(socket with threads outside) (pin with threads inside)

(pin with threads inside) (socket with threads outside)

(socket with threads outside) (socket with threads inside)

(socket with threads inside) (pin with threads outside)

(pin with threads outside) (pin with threads inside)

(pin with threads inside) (socket with threads outside)

(socket with threads outside) (pin with threads inside)

(pin with threads inside) (socket with threads outside)

(socket with threads outside) (socket with threads inside)

(socket with threads inside) (pin with threads outside)

(pin with threads outside)